Since the generative AI boom began, I’ve been on a journey- testing, tweaking, and experimenting with every tool I could find. Writing assistants, image generators, code writers, website builders, app creators and then finally, music.

The first AI music tools I tried were laughably bad, flat, offbeat, and soulless. But then they started getting better. Uncomfortably better. The kind of “better” that makes you pause mid-beat and go, “Wait, anyone can do this now?”

Let me visualise this for you:

Below, on the left, is Kweku Smoke’s Higher, I fed my own rendition of the instrumental, prompted it and added the lyrics, and it generated this choir rendition on the right.

That’s when it hit me: this isn’t just about innovation; it’s about disruption.

And not the kind that sparks new opportunity alone, but the kind that could completely reshape the economics of creativity.

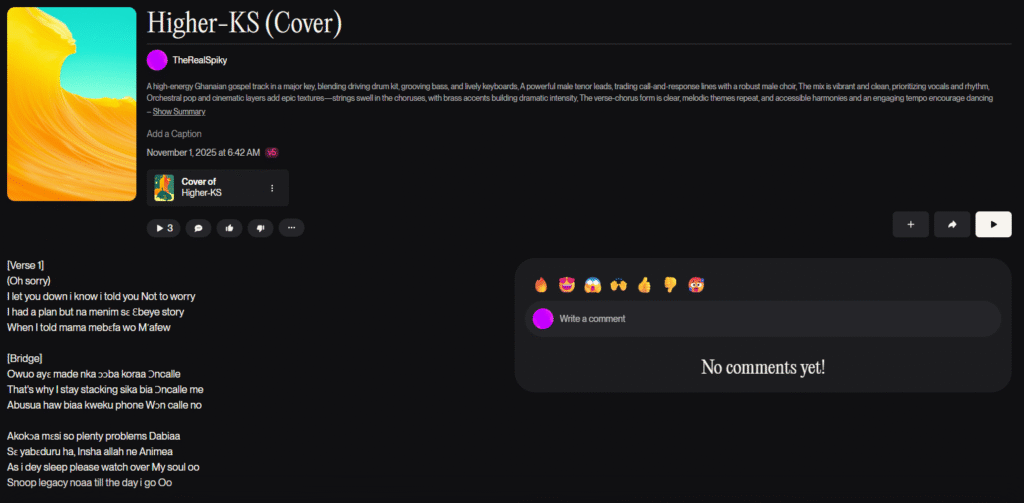

Here’s another example:

Below is an instrumental I produced

I uploaded it to Suno, wrote lyrics (with AI assistance) and described the persona of the singer and the vocal style and the results:

The Economic Reality: When Streams Turn to Trickles

Even before AI entered the studio, streaming had already turned the music industry upside down.

Once upon a time, artists sold CDs, cassettes or vinyl, one purchase, full price. Then came iTunes, pay-per-song. Then streaming, pay per thousand streams. Now, it’s pay per fraction of a pesewa, penny or cent.

Artists today are like a skilled Kente weaver who spends weeks perfecting a complex design and pattern, but is only paid for the few cotton threads used to tie the loom, while the final, expensive cloth is sold by someone else.

Producers who once charged thousands now fight for visibility on platforms like BeatStars, SoundCloud, etc.

And now AI enters the scene, capable of generating a full-length album in minutes.

So, what happens when a platform can mass-produce endless “Amapiano beats” or “Afrobeats type instrumentals” and doesn’t have to pay a single human?

It’s a digital gold rush, except this time, the miners are machines.

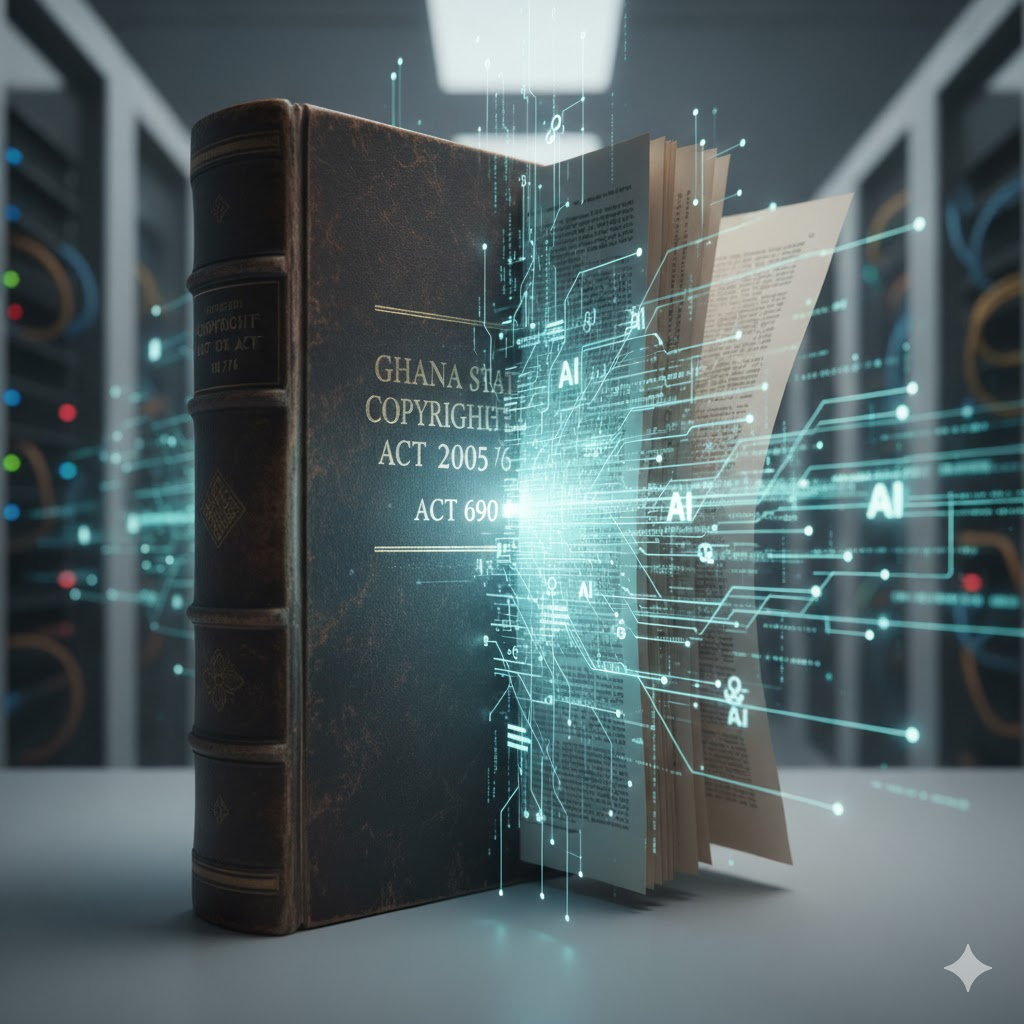

Copyright Wasn’t Built for Code

The scary part? Copyright laws were never designed for this.

Our legal systems assume a human creator, someone you can credit, sue, or negotiate with. But how do you copyright a song generated by an algorithm trained on a billion human songs?

It’s like trying to apply traffic laws to drones; the rules simply weren’t written for entities that don’t technically “drive.”

Who owns it, the developer, the dataset, or the ghosts of the artists whose work trained it?

And if a Ghanaian musician’s voice, melody, or rhythm becomes part of a global AI dataset, how do we track or compensate for that?

You see, this isn’t just an ethics issue anymore; it’s a policy gap. One that can’t be ignored much longer.

The Cultural Risk: When AI Erases the African Sound

Then there’s the cultural layer, the one that cuts the deepest.

If AI models are trained mostly on Western music, what happens to our sound?

Africa’s heartbeat lies in its rhythm, the fontomfrom, the dondo, the djembe, the kora, the talking drum, the subtle inflexions of Twi or Ewe melodies. These aren’t just sounds… they’re our DNA. They’re our stories!

However, if we’re not intentional about how AI learns, it could reduce all that to generic “Afro-inspired” presets, and that won’t be representation, that would be straight-up digital colonisation.

I mean, imagine a future where global AI systems keep generating “African-style” songs that no African artist benefits from, and worse, that sound nothing like Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, matter of fact, none of Africa.

We could wake up one day to find that the sound of our home has been remixed into something unrecognisable, owned by no one, available to everyone, but disconnected from us, the roots of the actual sound.

Culture isn’t just meant to be consumed; it’s meant to be credited.

Artists Must Become Multimodal Creators

Another shift we don’t talk about enough is how AI is changing the expectations of audiences.

Fans today don’t just want a song…

They want an experience.

Music alone is no longer enough.

A modern artist now needs to blend:

- sound

- visuals

- storytelling

- personality

- community

- technology

Artists are becoming multimodal creators, not single-format musicians.

If AI can make a beat in 10 seconds, then what sets you apart isn’t just the beat, it’s the world you build around it.

It’s your visual identity, your narrative, your authenticity, your culture, your presence, your ability to blend mediums in a way AI can’t replicate.

In this new era, the artists who thrive won’t be the ones who do one thing exceptionally well.

It’ll be the ones who create ecosystems around their art.

Experiences.

Moments.

Stories.

Multimedia identities.

And ironically, AI can help with that.

The Solution Gap: Towards a “Creative ID”

Here’s where I believe the real innovation needs to happen.

If AI is being trained on human creativity, then the humans behind that creativity deserve to be recognised and rewarded. Every artist, producer, writer, and designer whose work feeds an AI model deserves a share of that creative economy, not just applause for “inspiring” it.

This will be an incentive to get more sounds willingly contributed to an AI training dataset.

Imagine a Creative ID, a blockchain-powered system that fingerprints every piece of creative work you release: your song, your voice, your artwork, your video, your beat.

Once your work is registered, it becomes traceable across the digital ecosystem. When an AI model uses it for training or reference, that use is logged. Whenever an AI-generated output borrows from it, a melody, a chord progression, a vocal texture, even a drum pattern, the system recognises that influence and allocates royalties accordingly.

Now picture this:

- A young producer in Kumasi uploads a beat he made on his phone. It’s tagged and registered under his Creative ID. Months later, an AI model trained on a global Afrobeats dataset generates a rhythm that includes patterns statistically similar to his. That use is logged, and the Ghanaian producer earns micro-royalties each time that rhythm is used commercially.

- A singer from Taa’di trains an AI voice model on her vocals. Later, a user in Japan generates an AI Afro-gospel track that mimics her tone and phrasing. The Creative ID system detects the match through embedding similarity, which is basically a mathematical fingerprint comparison, and automatically allocates credit and revenue, just like YouTube’s Content ID does when someone uses your song in their video.

- Or imagine if Hammer’s chord structures or Appietus’ drum patterns influence an AI-generated beat. The Creative ID ledger traces the model’s training data lineage, detects those references, and credits them accordingly. If 10% of the output’s sound profile statistically aligns with Hammer’s production style, he receives 10% of the royalty pool from that generated work.

This isn’t just a dream. The technology already exists in fragments.

In fact, Creative ID is simply the AI-era evolution of sample clearance.

Sampling taught us that you don’t need to replicate an entire song to owe the creator; even a small influence deserves recognition. If you use someone’s melody, you clear it. If you borrow someone’s groove, you pay for it. If your track is built on their foundation, they share the reward.

AI is sampling at a massive scale… except the artists whose work built these models currently earn nothing from it.

Creative ID would update the rules, not replace them.

Audio fingerprinting, like Shazam and YouTube’s Content ID, already identifies reused or derivative works.

Data lineage tracking, emerging from research labs at MIT and in Adobe’s Content Authenticity Initiative, allows files and datasets to carry provenance tags showing where training data came from.

Embedding similarity analysis, used in AI labs, can measure how close an AI’s output is to its training inputs, allowing influence to be quantified.

And blockchain offers an immutable record to log all of this transparently, with smart contracts that automate payment distribution.

Combine these technologies, and you get the foundation for a Creative ID ecosystem.

Now, imagine if Africa led this charge, building an African Creative Registry that plugs into a Global Creative Ledger linking to global AI databases. Every registered artist, beatmaker, writer, or filmmaker would have their creative DNA recorded, protected, and monetised.

So when an AI in Los Angeles generates a track “in the style of Afrobeats,” it’s not just drawing from the void; it’s pulling from a ledger of African creators, with traceable attribution and fair compensation.

The hardest part, of course, is measuring how much influence a creator’s work has on a generated output. But that, too, is being solved. Researchers are developing systems that compare the “creative DNA” of AI outputs to their training datasets, like a digital paternity test for ideas.

If removing your data from a model noticeably changes its style or quality, that becomes quantifiable proof of influence. And that’s how future royalties could be determined, based on influence weighting, not just direct copying.

In simple terms, if your fingerprint is in the data, and that data shaped the final product, you earn.

As I said earlier, it’s the same principle that revolutionised music decades ago with sample clearance. Hip-hop didn’t collapse under lawsuits; it evolved into one of the most profitable genres because it learned to pay for influence.

Creative ID can do the same for AI, turning what feels like creative theft today into a system of creative collaboration with accountability built in.

Because if AI can reference your art, it can also recognise your name.

And if it can recognise your name, it can pay you.

Let’s Move from Fear to Collaboration

One thing I deal with every day is people who consider AI a threat; not every change is a threat.

When the drum machine came, people said it would kill live drummers. It didn’t. It created new genres like house, techno, and hip-hop.

When Fruity Loops (FL Studio) and other DAWs came, they said it would end studio sessions. Instead, it birthed a generation of bedroom producers who redefined modern sound and invented new genres.

Think dubstep, trap soul, liquid DnB, Lo-Fi Beats, etc.

AI is just the next tool to possibly birth the next instrument.

It’s not the enemy; it’s the evolution.

The real question is, will we learn to play it?

Like electricity in the early 1900s, AI isn’t replacing creativity; it’s powering it differently. Some people will fear the shock; others will light up cities with it.

My Own Journey

I know this because I’ve lived it.

I started making film scores and beats with nothing but a laptop and headphones. I learned to compose, mix, and master from tutorials and long nights of experimentation.

Technology didn’t replace my creativity; it amplified it.

But even then, it was still me.

The ideas, the emotion, the imperfections, that’s what made the music human.

AI can simulate style, but it can’t simulate soul.

That’s why the best future is one where human soul meets machine precision, where creativity becomes collaboration, not competition.

Redefine, Not Resist

So this isn’t a warning.

It’s an invitation.

We can’t stop AI, but we can shape it.

We can build systems that reward authenticity, protect culture, and redefine creativity.

This isn’t just about protection; it’s about participation.

We’re not just fighting to preserve art; we’re helping design the next creative economy.

Because the future of music shouldn’t be AI versus artists.

It should be artists with AI.

Every revolution, creative or whatever, starts with fear.

But fear is just an unclaimed opportunity waiting for direction.

AI isn’t here to steal our voices; it’s here to test whether we genuinely understand what makes our voices matter.

And if we do this right, this era won’t be remembered for AI replacing artists.

It’ll be remembered for artists who rose higher… by creating with AI, not against it.